The High Quality Research Act and American Science

Yesterday, President Obama spoke at the National Academy of Sciences to mark its 150th anniversary. Alongside the usual issues, Obama took time to defend "the integrity of our scientific process" and "our rigorous peer review system."

Why? Because they're under attack—from within the halls of Congress.

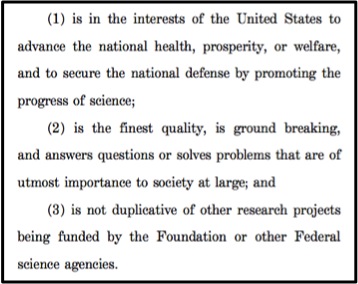

Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX) is preparing legislation that would disrupt peer review at the National Science Foundation (NSF). A draft of the bill—which is called the "High Quality Research Act" (HQRA)—leaked onto the web this week. It includes a new set of criteria for NSF projects:

There are all sorts of reasons these developments should be of interest to readers of this blog—not least, the fact that the NSF funds the history of science through its Science, Technology, and Society (STS) Program. Below, I'll fill out a few of the details of what's happened, and suggest some ways HQRA (and its discontents) link up with issues of concern to science studies more generally.

While Smith was apparently the least of three evils when he was appointed chair of the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, his views on climate change and other issues set him apart from the vast majority of practicing scientists like those Obama addressed yesterday.

Of course, this hasn't stopped him from joining Tom Coburn and others in an effort to redirect the NSF's extensive merit review system toward a set of goals defined by Congress. Late last week, Smith took the effort to a new level, though, when he wrote the Acting Director of the NSF about five projects whose "intellectual merit" (an NSF metric) he doubted. Here they are:

As the Committee's ranking Democrat pointed out in response, Smith's decision to question the scientific merits of specific grantees is unprecedented. "By making this request," she added, "you are sending a chilling message to the entire scientific community that peer review may always be trumped by political review." While peer review isn't perfect, she concluded, it's the best we've got.

Over the next few days, everyone—politicians and lobbyists, scientists and their societies, scholars and citizens—will no doubt be weighing in on what all of this means. Let me just highlight a few things that I think speak directly to some of the issues explored by science studies in general and this blog in particular.

It's worth noting that the five studies singled out by Smith all fall under the NSF's Directorate for Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences (SBE). Why does this matter? For one, it seems unlikely that Smith would have ventured such a salvo at "harder" sciences like math and physics (John McCain's 2008 beef with bears not withstanding).

For another, we're not far from the so-called "Science Wars" of the 1990s. Then, as now, the politics of knowledge were close to the surface—and the headlines. Though Sokal's famous "hoax" was perpetrated on behalf of peer review, its afterlife in the media juxtaposed "scientific" and "social" ways of knowing in a way that rendered (and renders) some "social scientists" anxious.

Another theme of interest to scholars of science studies is the notion of "peer review" itself. Interest goes back at least as far as Robert Merton's notion of "organized skepticism," one of the four scientific norms he introduced in "The Normative Structure of Science" in 1942. Merton extended that analysis in 1971, in a famous co-authored piece on "Patterns of Evaluation in Science."

More recently, STS scholars like Sheila Jasanoff have built on Merton by attending to the career of peer review in the realms of law and policy—or, more recently, in the contentious political climate around the issue of global warming. Jasanoff and others trace this evolution to the expanding circle of stakeholders as science and technology extend their reach.

Mario Biagioli provides an alternative perspective on peer review—including a useful overview of both its history and the literature attending on it. For Biagioli, the relevant questions are less those of stakeholders and politics with a capital-P (though they are relevant), and more the philosophical issues connected with questions of authorship and intellectual property.

In either case, science studies has had a great deal to say about peer review, and will no doubt have more to say in the weeks and months ahead. What interests me is how, in response to Smith's bill, the links between this thing called "the scientific process" and this thing called "peer review"—both contingent, even problematic concepts—tend to be shored up, not least by those (and here I'll just take myself as a data point) who have participated in historicizing and even criticizing those same concepts in other contexts.

Amidst calls for open access (including an ambivalent "trial" by Nature in 2006) and what seem like some pretty crucial questions about the merits and possibilities of the "scientific process" as it's currently practiced (op. cit.), the intrusion of capital-P politics still tends to reinforce old binaries and shore up otherwise unstable categories in the interest of protecting what we've got.

So, when Obama says "fields like psychology and anthropology and economics and political science" are all "sciences because scholars develop and test hypotheses and subject them to peer review," or when he says "we’ve got to make sure that we are supporting the idea that they’re not subject to politics, that they’re not skewed by an agenda," my interest is piqued.

Do we really believe that's what defines a science? Either way, do we really think whatever science is isn't "subject to politics" or "skewed by an agenda"? Or do we mean it at particular times, with respect to particular politics and agendas, when particular hypotheses are under attack?

I'm not sure, but wouldn't it be fun to see a colleague—a scholar of peer review, say—called up to testify on its history and its relative importance for "the scientific process" as a result of all this?