-Ome Sweet -Ome

We asked Evan Hepler-Smith, a historian of science whose work focuses on how chemists have used language, data, and method over the last hundred years, what the sort of questions he asks might reveal about contemporary science. He sent us the following guest post; you can find out more about his work here.

Recently, a small group of scientists has begun been laying the foundation of a new interdisciplinary field. Their ambitions include applying biological mechanisms to the synthesis of new drug candidates, integrating huge collections of biological and chemical data, and linking western pharmaceutical science with the study of traditional Chinese medicine at the molecular level. They call their new field “chemomics.”

So far, chemomics isn’t much more than a twinkle in the eye of a few pharmaceutical chemists, but it already has a catchy name, which makes one reflect on how, as Patrick McCray recently remarked, nearly everything seems to have an “-omics” these days.

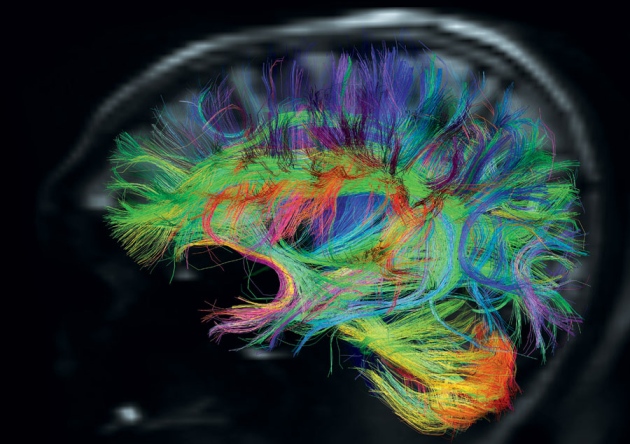

In the life sciences, there’s the proteome, the microbiome, the interactome, and dozens more (not to mention the genome – more on this ur-ome in a minute). -Omes have colonized neuroscience (the connectome) and cultural studies (the culturome). Like other trends in scientific terminology and method – the “molecular” sciences, “computational” fields, neuro-everything, and the many faces of translational medicine – -omes can be easy to scoff at. But they’ve attained impressive cultural, institutional, and intellectual stature, and that makes the suffix1 worthy of historians’ attention.

|

| The connectome: where “neuro-” meets “-omics.”(Source: http://www.nature.com/polopoly_fs/7.3435.1332258664!/image/brain.jpg_gen/derivatives/landscape_630/brain.jpg) |

The scientists have certainly been paying attention.

There are Wikipedia articles, a blog, and at least two journals dedicated to “-omics.” -Omes engage some of the most prominent themes in recent science, from Big Ideas to Big Data. In the inaugural issue of OMICS in 2002, the editor-in-chief explained that the mission of the journal was to “facilitate a forum for new voices, provide tools for networking researchers from diverse fields and industries, and act as a catalyst for innovative, perhaps even controversial positions.”2 The homepage of Nature’s now-defunct -Omics Gateway explains, with British candor, “Many of the emerging fields of large-scale data-rich biology are designated by adding the suffix ‘-omics’ onto previously used terms.”

There are Wikipedia articles, a blog, and at least two journals dedicated to “-omics.” -Omes engage some of the most prominent themes in recent science, from Big Ideas to Big Data. In the inaugural issue of OMICS in 2002, the editor-in-chief explained that the mission of the journal was to “facilitate a forum for new voices, provide tools for networking researchers from diverse fields and industries, and act as a catalyst for innovative, perhaps even controversial positions.”2 The homepage of Nature’s now-defunct -Omics Gateway explains, with British candor, “Many of the emerging fields of large-scale data-rich biology are designated by adding the suffix ‘-omics’ onto previously used terms.”

|

| Source: http://online.liebertpub.com/action/showCoverImage?journalCode=OMI& |

The best-known -ome is the genome, and it seems safe to trace the explosion of -omes, beginning in the mid-90s, to the Human Genome Project. (For example, OMICS began its life as Genome Science and Technology, edited by Craig Venter.) Most of the younger -omes are the fruit of both the HGP’s successes (its totalizing vision and enthusiasm for public-private collaboration) and failures (the considerable gap between knowledge of the genome and knowledge of the organism).

-Omes also seem to share certain structural features. Let’s return to chemomics.

Chemomics, write its proponents, is the study of molecular subunits with a specific biological function. Each such subunit is a “chemoyl”; the set of all chemoyls is the “chemome.” Chemomics studies3 the chemome “using approaches from chemoinformatics, bioinformatics, synthetic chemistry, and other related disciplines.”4

On this basis, we might sketch a tentative picture of what’s in an -ome. First, the -omemaker carves up some portion of the world into a set of atom-like units (chemoyls, the “molecular interactions” that make of the interactome, the n-grams of culturomics). These units should be accessible to study using familiar methods from one or more disciplines, like chemistry and statistics. Their treatment as a significant level of organization, however, is usually something new. The -omicist reassembles these units to build up a picture of the world (proponents of the chemome hype it as a “biological periodic table”). Finally, collaborators from different disciplinary backgrounds start investigating this -omeland, usually by generating, collecting, and interpreting Big Data.

-Omes derive significant rhetorical and conceptual power from an easy slippage between the levels of the individual, the community, and the abstract ideal type. (The contributors to Keith Wailoo, Alondra Nelson, and Catherine Lee’s new volume on genetics and identity have explored some consequences of this slippage.) And they tend to make use of powerful metaphors (like the “biological periodic table”), often derived from traditional disciplines, to describe their entities and arguments.

|

| From the genome to the microbiome, we are all -omebodies. (Source: http://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu/Custom/ProductImageHandler.ashx?ProductID=4098&endHeight=270&endWidth=190 ) |

Interdisciplinarity is a challenging topic for historians of science used to arguments (and source bases) framed in disciplinary terms (though this hasn’t stopped Cyrus Mody, among others, from tackling it effectively). -Ome studies (-omework?) could be a productive route for advancing the study of interdisciplinarity, popularization, and Big Data in recent science.

A careful look at chemomics, for example, could tell us something about the nexus of the multinational pharmaceutical industry, traditional therapeutics, state funding of science in China, the cultural authority of the life sciences, and the translation of computational methods and data between fields. The same could be said for better-known -omes, and for the other clusters of fashionable new fields mentioned above. At the very least, all those neologisms make tempting targets for some old-fashioned free-text-search culturomics.

A careful look at chemomics, for example, could tell us something about the nexus of the multinational pharmaceutical industry, traditional therapeutics, state funding of science in China, the cultural authority of the life sciences, and the translation of computational methods and data between fields. The same could be said for better-known -omes, and for the other clusters of fashionable new fields mentioned above. At the very least, all those neologisms make tempting targets for some old-fashioned free-text-search culturomics.

———————————————

[1] An etymological tangent, per the OED: the Greek -oma, a generic suffix for converting verbs into neuter nouns (e.g. diploma), made its way into English mainly in the form of Greek medical terminology, particularly swellings and tumors (carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma). In part through the influence of French and German forms, the variant -ome began to pop up, and got attached to the names of specific structural elements of plants or animals (rhizome, chromosome). “Biome” and “genome” were coined in the early twentieth century, and in somewhat different ways, both expanded the sense of -ome from “part” to “part-that’s-also-a-whole.”

The resemblance of –ome and –omics to the -nomy and -nomics of economics is an etymological coincidence but surely didn’t hurt the popularity of either suffix.

[2] Eugene Kolker, "Editorial," OMICS A Journal of Integrative Biology, 6:1 (2002): 1.

[3] -omics literature seems to be rife with pseudo-passive constructions like this; there are “-omes” and “-omicses” but not many “-omicists." What are the stakes of choosing a name for a practice that does or doesn’t lend itself to a name for practitioners?

[4] Jun Xu et al., “Chemomics and drug innovation,” Science China Chemistry 56:1 (January 2013): 71-85.